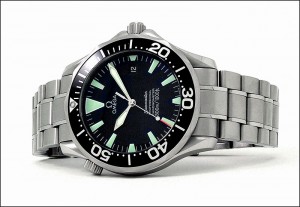

While my collecting interests now mostly focus on vintage watches, my habitual “daily driver” for the past several years has been my trusty Omega Seamaster Professional 300M diver. As much as I like my vintage watches they can of course be a little finicky and the lasting degree of water resistance is typically questionable at best. So I wanted something that could be depended upon without worry when I needed it or else at least without worrying about defiling an irreplaceable original. And I thought perhaps there was probably a little something to be said for owning at least one Omega from new as its sole owner, so a modern Omega diver seemed a logical choice.

It’s now been a little more than four years since I purchased it while on a Caribbean vacation (not the best way to purchase an Omega BTW but I didn’t know better at the time!). And as the 5-year mark has started to approach I began wondering if I would heed the factory recommended 5-year service interval or else take fortune into my own hands and flirt with extending the interval.

But a few weeks ago I was invited to a gathering of collectors at an Atlanta watchmaker’s shop, and in the course of one of our discussions the owner and master watchmaker offered to test the water resistance of my watch. I cheerfully agreed, not only just out of curiosity but just wanting the satisfaction of knowing whether my watch was really and actually “waterproof

or not.

This particular shop serves as an authorized repair facility for a number of Swiss brands including Omega and as such was especially well-equipped. The typical regimen for testing the water resistance of dive watches is a 3-stage process and involves three sophisticated testing machines in order of increasing rigorousness.

The first machine was a sophisticated Witshchi ALC 2000 dry tester that by using air pressure alone carefully measures the miniscule changes in the shape of the crystal and case under pressure to determine if the gaskets are functioning as intended without even subjecting the watch to water exposure. My Seamaster passed this test (sort of) but indicated a potential fault as my watch didn’t quite behave as expected according to the program.

The second machine was the more commonly seen Bergeon “dunk” apparatus, which is often the sole means of testing in many lesser-equipped shops if they’re so equipped at all. This machine uses a pump to increase the air pressure in the test chamber to up to 3 times atmospheric pressure. After the watch is allowed to sit in the high pressure air for a bit high-pressure air will enter the case and increase the air pressure inside if a seal has failed. The valve on the test machine is opened, the pressure in the chamber is allowed to equalize and the watch is quickly dunked into the water below. If the watch has a water resistance fault a steady stream of bubbles will result as the high pressure air escapes but there is still almost no chance for water to actually enter the case. And unfortunately for me, this is exactly what happened with my watch — a steady stream of bubbles emanating directly from the helium escape valve on my Seamaster.

The third and final test (which we skipped of course on my watch after discovering the fault) would be a more realistic and potentially invasive test in which a watch that has already passed the previous tests is subjected to high water pressures. Following exposure the watch is heated and a cold drop of water placed on the crystal. If water has entered the case during the test condensation will form under the crystal. (Sorry I don’t have a photo here to illustrate, hopefully I’ll get one my next trip).

I suppose there are two morals to this story:

- The oft-cited manufacturer recommendations to have watches that are subjected to dives or habitual water exposure should be tested for water resistance annually are well-formed. The neoprene gaskets need to be inspected and changed periodically to continue performing as designed, and clearly they shouldn’t be depended upon to last 4 years as I’ve seen here.

- For quite some time I’ve had the opinion that the helium release valve on Omega’s modern dive watches is a goofy and superfluous gimmick that does little for the typical owner/user other than introduce one more possible point of failure to the system. It would seem that opinion was vindicated here, but perhaps that’s a topic for another post.

Very interesting article, however the HRV may not have been at fault. The HRV will be the place of least resistance for air to escape the watch, if there is a leak anywhere on the watch.

I bought my Omega Seamaster 300M about 6 years ago. Since then, I’ve had 3 occasions where water entered the watch. For the first two times, the warranty covered it. On the second repair, they said that it might be a faulty gasket. Well, this third time is out of warranty, but I’m afraid to take it in for repair at the Omega dealer, knowing that it might cost me US$ 500. I’m losing my faith in Omega watches. I will take my Rolex Submariner to dive next month, and see if it will hold.