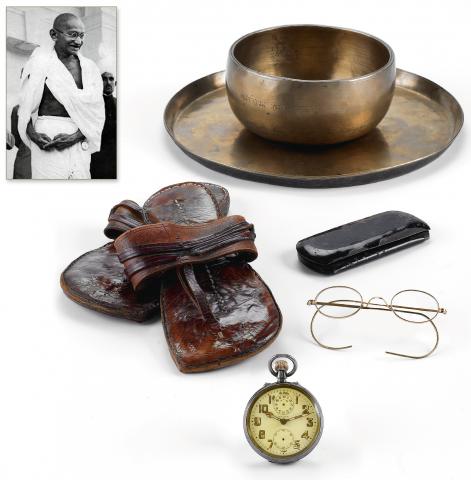

Antiquourm Lot #364 in the March 4-5 Auction: Zenith Alarm Pocketwatch, Eyeglasses, and Sandals described as having been owned by Mohandas Gandhi. Photo: Antiquorum.

Lot #364 in the upcoming Antiquorum auction March 4-5 in New York contains a Zenith pocketwatch, sandals, and “thali” plate and bowl that although outwardly unremarkable have what would be a fantastically unique provenance: they are attributed to none other than the great visionary Mohandas Gandhi. It’s the stuff of watch collector legend.

But given Antiquorum’s growing reputation for interpreting and describing fact in ways that benefit their own interests but aren’t necessarily supported by knowledgeable collectors or authorities (to say the least!), should we have any faith in Antiquorum’s description?

Short answer: I don’t know, but the depiction of the watch seems plausible.

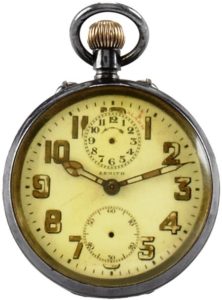

I find no problem with the watch itself as presented. It’s a Zenith pocketwatch with alarm complication described as dating to about 1910 or so, a period in which Ghandi would still have been practicing law in South Africa. Before becoming famous for their high-beat automatic chronograph calibers in the later half of the Twentieth Century, Swiss maker Zenith was known for simpler, respectable, and reliable if perhaps somewhat unremarkable timepieces in the middling price and quality range. A sterling silver-cased Zenith alarm pocketwatch indeed seems rather fitting for a lawyer-turned-visionary, originally purchased for its quality and practicality rather than ostentation. The condition seems to indicate it was then carried over much of the course of a lifetime, as might be expected for the humbly frugal man known for attention to punctuality.

The watch seems consistent with historical depictions. As reported by the Times of India, the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi describes the watch as a gift of which Gandhi was quite fond from Indira Nehru, an additional provenance tidbit that would make the watch even more notable. Ghandi himself described the watch as having a “a radium disc… and also a contrivance for alarm. It was a gift to me. The cost then was over 40/-. It was a Zenith watch.” Reportedly Ghandi was brought to tears (though perhaps more by loss of faith in fellow man than the material loss) when the watch was stolen while riding a train to Delhi in 1947, but it was later returned by the thief with a request for forgiveness to Ghandi’s delight.

Zenith-signed mechanical alarm movement. Note the sterling hallmark inside the caseback as well. Photo: Paul Boutros/Timezone.com

I can find only a few problems with Antiquorum’s description of the physical condition of the watch. For one thing the hairline cracks would seem to indicate a porcelain or enamel dial rather than “metallic” as stated, and it seems strange that the description fails to mention that both the alarm hand and subsidiary seconds hands are missing. The movement description states “oxydized (overhaul required, at buyer’s expense)” which seems fair enough, though it abstains curiously from stating whether or not it is actually running. If anything, the description might even be overly critical (if it’s in running shape at least), as much of the visible oxidation or rust seems confined to the steel alarm gong about the periphery of the movement, which is likely easily corrected and not likely to impact its functionality. The only really odd part in the condition report is that despite the faults noted it somehow cheerfully arrives at a summation of “Experts’ Overall Opinion: exceptional” when condition reports are usually expected to remain objectively focused on the actual physical state.

By now some measure of irrational optimism is probably to be expected. Antiquorum after all has been accused of failures of transparency in their descriptions and lackluster diligence in verifying the correctness of sellers’ claims in previous auctions. Among the controversial sales are the fake Omega Seamaster 300 with even more fake supposed Special Air Service provenance (lot #128 in the April 2007 Omegamania thematic auction), and more recently the inauthentic cobbled-together “Heuer” Index-Mobile outrageously described as “custom made” (Lot# 39 in the November 14-15, 2008 auction). So given this history, it could be wise to take Antiquorum’s descriptions with a considerable grain of salt.

But I’d like to be able to think that Antiquorum went out of their way to research the authenticity of this lot and the veracity of the seller’s provenance claims. There are after all many, many Gandhi scholars with the expertise necessary to authenticate these items, and there are many, many photographs of Gandhi taken over the course of his lifetime against which to compare. And after all, to knowingly auction a watch and items falsely attributed to a man as great as Gandhi would be a whole new order of blasphemy that I would hope not even Antiquorum would dare flirt with. To do so could upset the entire world, ruining an auction house’s reputation even among non-watch collectors if it were found out. In fact, I’d hope that Antiquorum was especially and unusually diligent in authenticating this lot. It’s not clear to me if it’s wise to assume they did.

In the Antiquorum-owned Timezone.com preview of the auction, Timezone representative Paul Boutros describes the Zenith pocketwatch as being accompanied by a letter of authenticity:

“A Zenith alarm pocketwatch in fair condition, but with an extraordinary provenance. The watch was owned by Mahatma Gandhi, who always had it attached to his loincloth. It was given to his grandneice[sic], Abha Gandhi in the 1940s. Abha was his assistant for six years, and he died in her arms when he was assassinated. Abha willed the watch to her daughter, Gita Mehta upon her death. Gita wrote the letter of authenticity accompanying the watch. Here’s an extract from the letter:

‘Herewith, I declare that the silver pocket watch was presented by Mahatma Gandhi to my mother in the 1940s. My mother, affectionately called “Abhaben”, was the young woman on whom Gandhiji used to lean and in whose arms he died.’“

Notably however, a strict reading of Antiquorum’s own description of the watch does not seem to explicitly describe such a letter as pertaining to the watch, which seems oddly out of place for an auctioneer specializing in watches. Perhaps it’s a simple oversight; perhaps a single letter of authenticity covers both the watch and the bowl/thali set. Since the full text of the letters themselves is not provided, it can’t be said for certain.

If anything, I’m far less suspicious about the watch than I am of the eyeglasses, which lack the iconic round shape. Instead, they’re quite plainly elliptical. I’ve no reason to discount the authority of the certifying authorities, but even a cursory examination of the publicity photos Antiquorum provides reveals that the elliptical/oval shape of the glasses presented for auction conflicts with the depiction of Gandhi shown right in the photo, in which he wears the expected round-shape spectacles and carries a (the?) pocketwatch. I suppose it’s entirely possible that Gandhi may have owned several pairs of eyeglasses in the span of a lifetime, but in a quick survey I was unable to find a single photograph showing Gandhi wearing anything but the more typical round eyeglasses. I have no explanation for this apparent anomaly.

Eyeglasses sold in the upcoming Antiquorum auction attributed to Gandhi. Note the elliptical shape. Photo Paul Boutros/Timezone.com

The auction estimate of $20,000 – $30,000 USD seems astonishingly low, if not conspicuously so. Gandhi famously made a point of owning as few material possessions as possible, making the few that remain enormously rare. The auction lot consists not only of the Zenith pocketwatch, but also the famously iconic eyeglasses, sandals, and the thali and bowl as well. The provenance attached to an enormously notable historical figure would presumably extend interest in the lot well, well beyond watch collectors. Especially when estimates of several lots in the same auction are well into six figures, and one even into seven figures (it is after all the Graves Patek Philippe, but still the stark contrast seems notable). Something seems at least a little off here with the estimate then; I can’t explain it. Perhaps they’d simply like to be able to report later that it sold for several times the estimate.

It would also seem to me to be extremely odd that descendants of one of history’s most famously humble men would have sold mementos and memorabilia pertaining to Gandhi to private collectors who would in turn auction them. Though not trained as a theologian it seems to me to be absolutely at odds with the great Mahatma’s teachings that his few earthly belongings might be sold for profit into private hands rather than placed in a museum or remaining with the original recipients. It seems downright strange, if not nearly unthinkable, for his descendants to have done so. I have no explanation for this either.

And some in India would seem to agree with me: news of the auction has caused quite an uproar in India, and the sale is being decried as a travesty. Many were apparently surprised to find that the items in question were not only not in India but in private hands, and even more surprised that an abnormality of law designed to prevent trafficking in historical treasures may impede their return to India if purchased by a private individual. As yet, however, I haven’t seen much of any question of the authenticity of the claims of provenance.

It’ll be interesting to see how this one turns out.

Hi Rrryan – Something does not seem right with this. It is at odds with historical records.

Pls check out my blog on ths – the update today

http://maddy06.blogspot.com/2008/06/gandhijis-ingersoll-watch.html